Dr. Scott Savitz’s November 16, 2022, RAND article on drifting mines can be found here. Naval News also has a few stories on the topic of mines here. According to Dr. Savitz…

“Drifting mines are extraordinarily hard for navies to counter, since most mine countermeasures capabilities are designed to counter fixed minefields. A traditional mode of countering drifting mines involves having sailors stand watch, scanning the waters around the ship. When they detect a nearby mine, the ship can turn to avoid it, use a water cannon to push it away, or try to sink or detonate it with gunfire. However, it is hard to spot a dark, semi-submerged object—especially at night, in foggy conditions, or in turbid waters. Moreover, if the mine’s designers were clever, they will have adjusted its buoyancy so that it is entirely submerged beneath the surface, making it still harder to detect.”

Dr. Scott Savitz’s RAND article on drifting mines

Naval News reached out to Dr. Savitz in late November 2022 for additional comment and analysis on his RAND article.

Naval News: How are the U.S. Naval Forces prepared or not prepared to counter drifting mines?

Dr. Savitz: Drifting mines are inherently harder to counter than fixed mines. The vast majority of mine countermeasures (MCM) involves either minehunting (searching for mines, usually with sonar, then neutralizing them individually) or minesweeping (dragging gear through the water to prematurely detonate influence mines, which respond to ships’ acoustic, magnetic, and other signatures). Both are predicated on the mines staying in place. The primary defense against drifting mines is the same as it has been for over a century: ships try to detect potential drifting mines in their vicinity using sailors with binoculars or various sensors, then try to shoot the mines with available weapons and/or avoid them. As a complementary tactic, bow rakes have sometimes been attached to ships, so that drifting contact mines will detonate at a distance from the hull, but this impairs ship hydrodynamics; I don’t see anyone doing that today. Drifting mines can be hard to detect, depending on environmental conditions, and particularly if the mines are drifting slightly below the surface. There is also a risk of a high false-alarm rate: detritus can be mistaken for mines, and repeated false alarms can ultimately lead to complacency. Weapons targeting drifting mines also have to be capable of shooting at the correct horizontal and vertical angles, which can be difficult to achieve, particularly if multiple mines are detected, and drifting objects can be elusive targets, especially if they’re subsurface. Given these circumstances, the drifting mine problem is a hard one, and all nations could get better at countering these devices. I can’t speak publicly on the limitations of one nation relative to another.

Naval News: Are NATO or RIMPAC allies better prepared to counter drifting mines and can the U.S. learn from them and their ships and equipment?

Dr. Savitz: There are a number of possible countermeasures that might be considered. This is not a comprehensive universe of countermeasures, only a few initial ideas.

- A combination of intelligence and detailed oceanographic data may aid in anticipating the threat and enabling ships to avoid areas with high concentrations of drifting mines.

- Ideally, the minelaying operation could be targeted before the mines get into the water, but while it may be possible to target some of the mines some of the time, it’s very hard to prevent all of the mines from getting wet. Minelaying, whether using fixed or drifting mines, can be a low-signature, distributed operation that is hard to prevent.

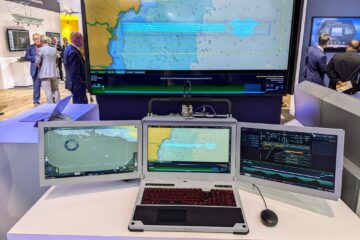

- Ships could employ short-range, sensor-studded uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) and uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs) to roam around in their vicinity, increasing detection range and accuracy. The two are complementary: the UAVs would have the better vantage point and speed for wide-area observation or focusing on a potential contact when needed, while the USVs could detect both surface and sub-surface threats.

- Those UAVs and USVs, or others, could also be equipped with remotely controlled weapons to target drifting mines. Pairs of USVs could also be used to catch drifting mines in nets; it might be advantageous to use pairs of them for this. These USVs could be subject to a high attrition rate from the mines, so they should be designed to be inexpensive, with limited capabilities. Alternatively, a number of really inexpensive USVs could roam in front of a ship with the intention of colliding with any drifting contact mines before they reached the ship–they would essentially be offboard bow rakes.

- Such USVs could also have gear attached to emit large signatures, enabling them to detonate drifting influence mines, but that gear and the need to handle it would render them more expensive.

- Once they have been detected, using water cannons to push them away from a ship. The effectiveness of this varies, particularly if the mines are sub-surface.

Naval News: What countermeasures do you propose NATO and the U.S. adopt to counter drifting mines?

Dr. Savitz: The lowest-hanging fruit from the above involves offboard UAVs for drifting mine detection and classification. Ships already launch UAVs, though they might need different ones for this purpose, or might need to put different sensors on them. Those UAVs could be small and cheap. Other potential acquisitions described above would require more research and development.

Naval News: Are there any laws of the sea, treaties, politics, or diplomatic channels the West can use to prevent drifting mines?

Dr. Savitz: The Hague Convention of 1907 is the most important document in international law regarding these systems. It forbids laying drifting contact mines unless they become harmless within one hour after release. Most major nations have signed and ratified the treaty, but non-state actors have not, and some nations may either defy or bend the treaty. The treaty mentions only contact mines (influence mines didn’t exist yet), so a nation may claim that drifting influence mines are permissible, even if it violates the spirit of the treaty. China has drifting mines in its inventory, as may other nations. Incidentally, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 banned different aspects of chemical warfare, which signatories defied during World War I (sometimes claiming loopholes).

Naval News: How about utilizing marine mammals to detect and neutralize these mines?

Dr. Savitz: I have tremendous respect for the minehunting marine mammals (see this RAND article on this marine mammal topic). However, they are trained to counter fixed mines, and I can’t envision any reasonable tactics for having them counter these mines. While that could conceivably be a failure of imagination on my part, I’ve worked with their handlers and other mine warfare stakeholders, and never heard any suggestion of them being used in that way.”

Dr. Savitz concludes in his RAND article on drifting mines…

“The most desirable approach of all is to prevent drifting mines from entering the water. However, releasing drifting mines is easy, and the main signature is a splash. They can be readily pushed off of almost any ship or pier, though a crane may be necessary to handle them in some cases. While it may be possible to detect and target some releases, the probability of entirely preventing them is very low.”