Russia’s latest warships are engaged in tests of a new hypersonic cruise missile. The tests are taking place in the icy waters of the Barents Sea, one of the remotest places on earth. They are under the cover of the long artic night, and beneath a thick layer of cloud. And yet they are being watched. And not just by NATO submarines (which of course cannot be confirmed).

OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) uses publicly available data to get insights into military capabilities. We are accustomed to the commercial satellite imagery used by map programs and Google Earth. And it is intuitive that those can sometimes be used to reveal military secrets. But they cannot see through cloud, or at night. For that, other less well known commercial satellites can be used. These ones, which use a technology called Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), cover areas which are hidden from the regular imagery satellites. In essence they use radar to see through cloud, and at night. The arctic winter is no protection from SAR satellites.

The main OSINT source is the pair of Sentinel-1 satellites. These are part of the European Radar Observatory for the Copernicus joint initiative of the European Commission (EC) and the European Space Agency (ESA). The data is freely available on the internet.

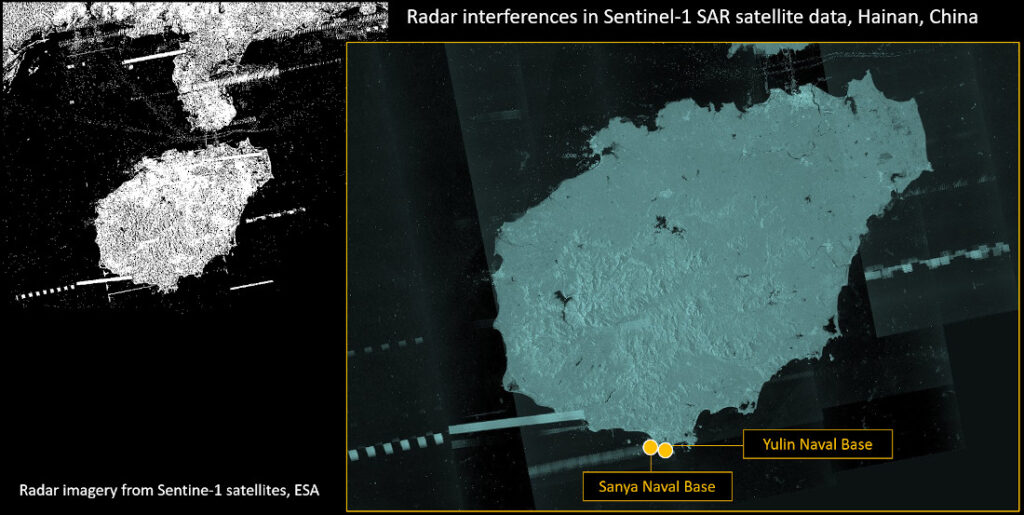

Sentinel-1 satellites have a weakness which can be turned into a strength. They can be temporarily blinded by other radar transmissions. It may obscure the picture, but it has an unintended benefit that it can be used to locate, and sometimes identify, the radar in question.

Top tier militaries have been using technologies like this for years. Their purpose designed satellites may be able to detect and categorize a range of radars. Sentinel-1 is limited by comparison. It only transmits at 5.4 GHz, with a 100 MHz bandwidth so only other radars transmitting at 5300-5500 MHz interfere with it. In other words, it only picks up radars which happen to be operating on similar frequencies to the satellite itself.

Like most information sources in OSINT, we shouldn’t focus on what it cannot do, but what it can. Even with its relatively limited sensor picture, it can reveal military secrets. And if the observers have strong technical skills, which some do, then it can be transformed into a rich intelligence picture. This is especially true when combined with other OSINT sources.

The technical tools developed by analysts include one called 5Ghz Interference Tracker developed by OSINT Editor. This overlays multiple Sentinel-1 images and uses algorithms to differentiate the signals. Among the things this makes possible is getting fixes on static radar sources.

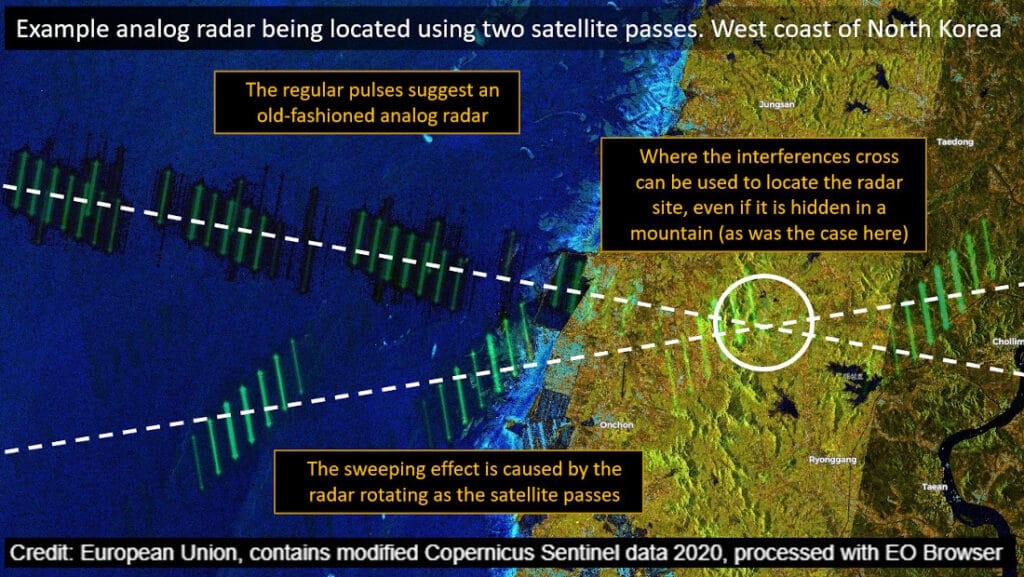

A lot can be gleaned from the images. The width of the interferences and pulse repetition helps identify the system. Older radars, which are analog and tend to be more repetitive, can be easy to classify. You can even make out the way that they are rotating as the satellite passes by. More modern radars, which incorporate anti-jamming techniques, give off a more confusing pattern. This doesn’t always mean that they cannot be identified.

Fixed site radars can be located by cross-referencing multiple satellite passes. As a rule, the interferences form a band running straight across the image. So if there are two satellite passes, from different angles, the X where they cross marks the spot where the radar is. Coupled with high resolution commercial satellite imagery (such as Google Earth), the radar can be identified. Or at least narrowed down. Even if a radar cross-fix is not possible, the source can often still be determined by searching along the path of the interference.

Ships are harder to cross reference because they move. However, in some cases the type of warship can be determined. Typically the context, and other OSINT data, is used for the initial identification. Some of the warships which can be seen are among the latest and most capable in their respective navies.

It is not just in the Russian arctic where these techniques can be applied to gain open source intelligence on the naval situation. Warships off the Chinese coast, or off Libya, or land based radars overlooking waters are also under the spotlight.

Open source intelligence can pose a threat to naval operations of any nation. It is free available and, largely, easily analyzed. Anyone with an internet connection can potentially locate warships in operational settings. Radar satellite data is not the most intuitive, but it provides OSINT watchers with yet another tool to track navies. And no navy is immune from OSINT.